New Year’s has often been a working holiday for American statesmen. More than a day of moral resolution, January 1st marks the anniversary of several bold, ambitious actions that have opened new eras and horizons for Americans as a people.

1. SCOUTING THE WEST

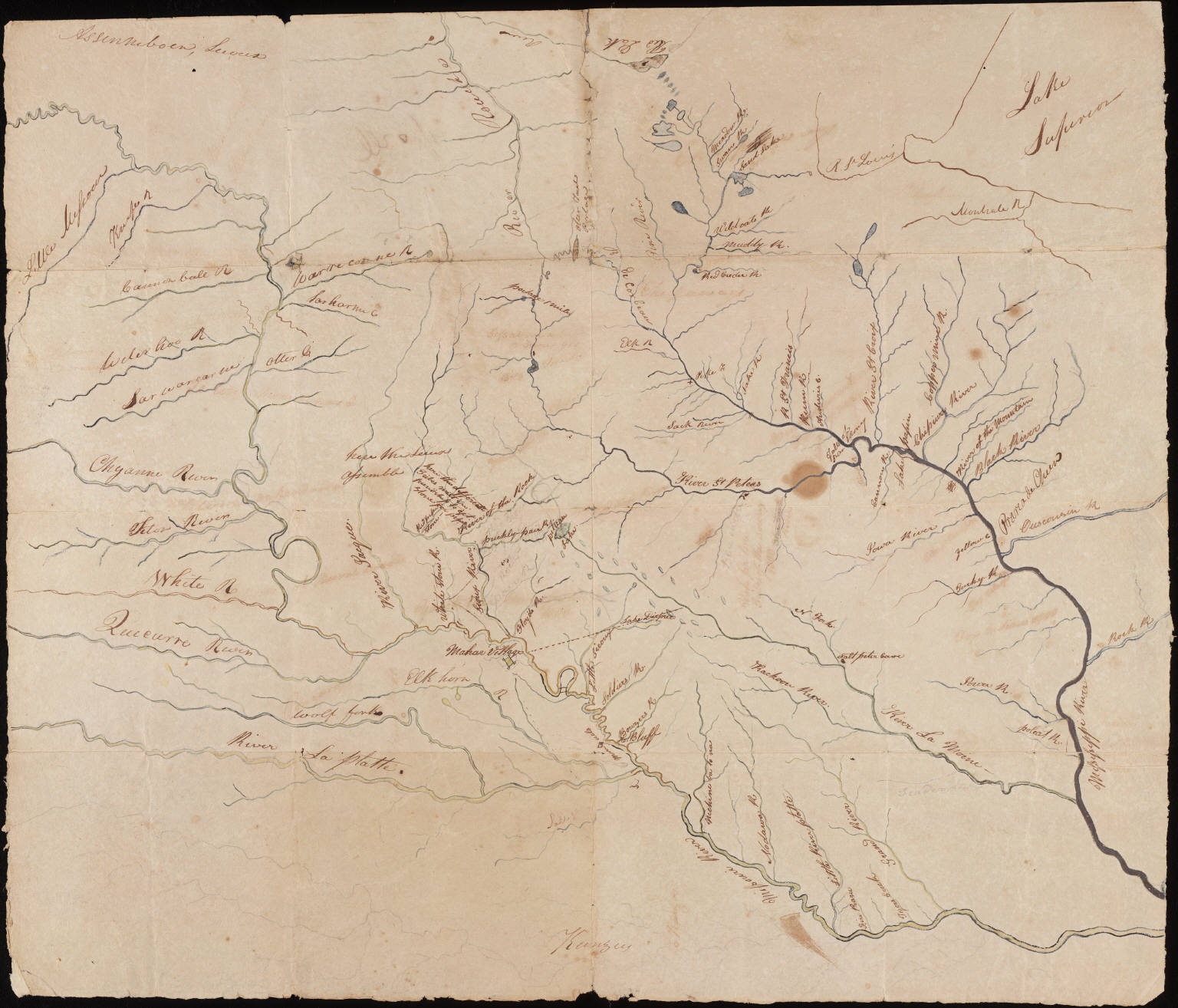

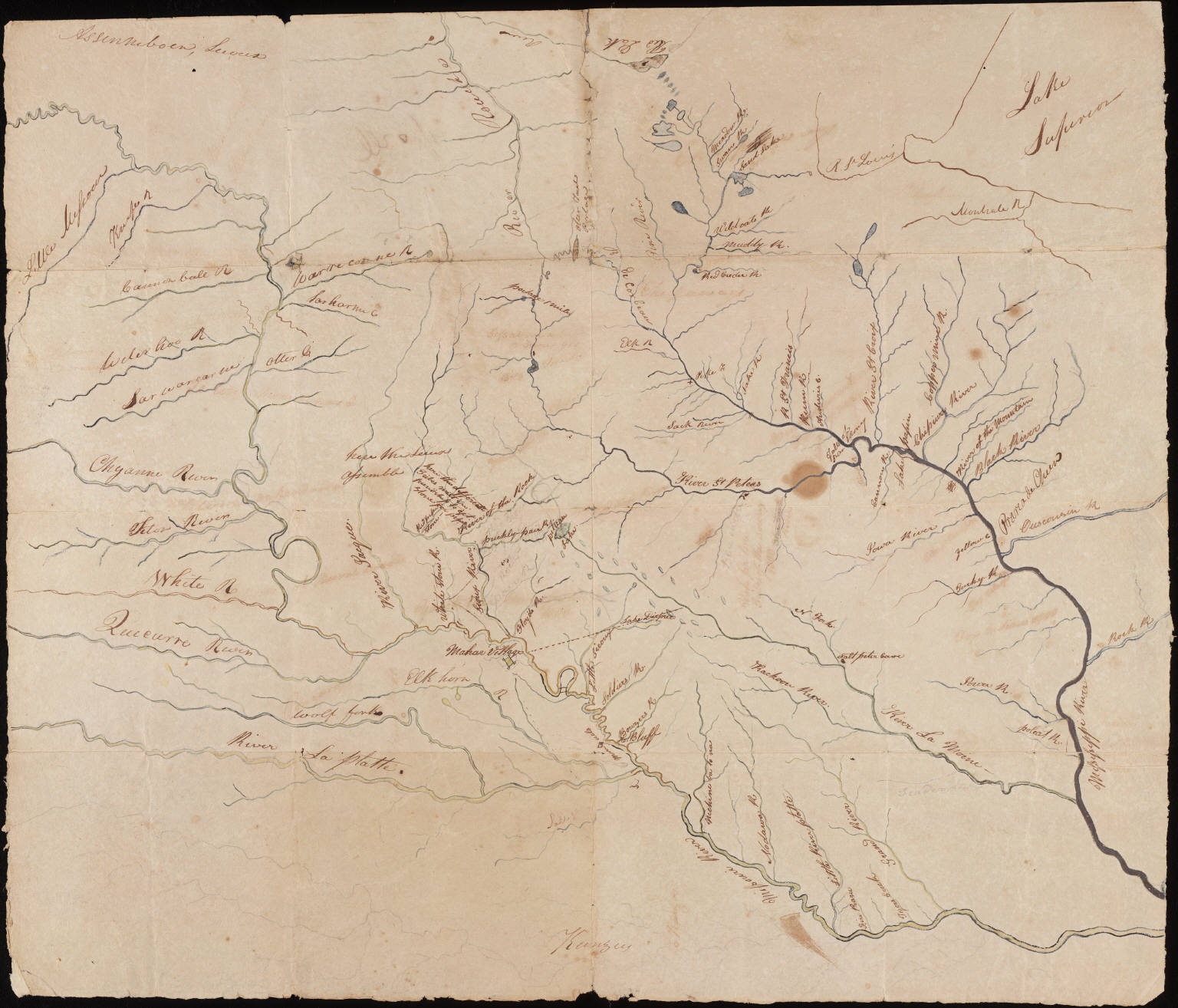

New Year’s Day in 1803 found Thomas Jefferson secretly laying the groundwork for the Lewis and Clark Expedition, a scheme that had to be covert because it proposed scouting out vast tracts of land that at the time belonged to other countries. The French lands now referred to as the Louisiana Purchase would not belong to the United States until the spring, while the Oregon Territory would remain the property of England for many decades. Yet Jefferson was undeterred in his determination to familiarize himself with, and strengthen American claims to, these unknown neighboring regions.

So he began crafting a confidential message to Congress, describing the possible benefits of reconnoitering these lands and asking for an appropriation of the $2,500 necessary to supply the journey. Congress looked with favor on his request, thus inaugurating a initiative that pioneered knowledge of the West’s lands, resources, and native peoples.

The government was rewarded with a treasure-trove of maps and documents that facilitated its later dealings with, and gradual displacement of, native American tribes. Today, we tend to discount the expansionist ambitions that motivated Jefferson, instead lauding the Expedition as an early model of the many progressive scientific projects and surveys the US government would subsequently fund.

2. FREEING THE SLAVE

Sixty years later, President Lincoln spent New Year’s Day greeting callers to the White House and putting his signature on the final version of his Emancipation Proclamation, which was sent out over the telegraph wires later that day. Not unlike the Lewis and Clark expedition, Lincoln’s statement had had a long fruition, with earlier drafts of the measure being floated and discussed the previous fall. Lincoln’s determination to associate the waging of the Civil War with the moral cause of ending slavery marked a tipping point in the long struggle to secure for African-Americans personal freedom and civil equality, a struggle begun decades earlier and continuing on for more than a century, even down to today.

The executive order, which famously declared the freedom of all slaves held in rebel states, was on display at the National Archives in Washington yesterday, on the occasion of its 150th anniversary. Though limited in its scope and practical effects, the proclamation spelled liberation for a people who had suffered oppression since colonial times. Lincoln’s deliberate blow to slavery paved the way for its complete and permanent abolition, accomplished through the ratification of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution.

3. WELCOMING THE IMMIGRANT

Finally, on New Year’s Day in 1892, the first immigrant (of some 16 million) passed through the doors of Ellis Island. It is commonly said that “American is a nation of immigrants,” but the establishment of Ellis Island and other formal points of entry gave that rite of passage a dignity and regularity that was previously missing.

Located near the Statue of Liberty, Ellis Island bestowed welcome and the necessary paperwork on immigrants who had previously been less distinguishable from American citizens. At a time when many born Americans went through life without the legal documentation of a birth certificate, Ellis Island conferred a bureaucratic identity on the newly arrived, routinizing a more paper-bound and legalistic conception of Americanness that is with us still. Today, however, Ellis Island stands as a cherished symbol of the rational means the government employed to bind its disparate population into one people.

May these complex and impressive projects inspire today’s political leaders to lift up their sights and grapple bravely with the issues confronting the nation now.